Death and bereavement are difficult facts for parents to teach small children, made harder still if they are grieving themselves. But many authors have found elegant ways to start the process

Dealing with death, in picture books and early readers, is a challenge for parents and publishers alike. There’s often a knee-jerk feeling of revulsion to contend with – “That’s a bit dark”, or “Surely they’re too young for that?” – the readerly equivalent of the sign against the evil eye.

But toddlers and pre-schoolers are likely to encounter some form of loss, even in their early lives – whether in animal form, or when a grandparent or even a parent dies. For a choked-up, grieving adult, or for one who wants to prepare a child for life’s only inevitability, a well chosen book can speak volumes.

Books dealing with the loss of someone close, especially a parent, are probably needed only in the dreaded specific situation, since reading a story in which a parent dies (outside the safely formula-bound, once-removed world of fairytale) is likely to induce fearsome anxiety in young kids. They’re hard going for adults, too: I only have to hear the title of Elke Barber’s Is Daddy Coming Back In A Minute? to feel a nose-prickling urge to stick my head under the pillow. But Barber’s book, which uses her son’s own words to ask and answer questions about death, is extraordinary, laying out with clarity and tenderness the anxiety, curiosity and unavoidable, drawn-out sorrow that a parent’s loss brings in its wake. Her second book, What Happened to Daddy’s Body?, also deals directly and sensitively with the realities of burial and cremation.

Similarly, Rebecca Cobb’s Missing Mummy, for the youngest children, and, Holly Webb’s A Tiger Tale, for slightly older readers, focus clear-sightedly on children’s fears, curiosity and feelings of being cut adrift. Webb’s book, about a little girl who’s lost her grandad, deals sensitively with the discomfort of grief’s etiquette, too: Kate is bemused by adult mourners laughing at fond memories, unsure whether and when she is allowed to feel happy.

But what about pre-emptively dealing with death, in more general terms – is it a good idea, or one that generates more anxiety than it allays? Personally, knowing that a much-loved but ancient Jack Russell was soon to be no more, I prepared the ground with my two-year-old, who had already begun to ask questions about what memorials meant. I found myself floundering when I tried to answer these, either overcomplicating matters or abruptly changing the subject (“Oh look – a squirrel!”). I am not a Christian, and didn’t really want to suggest dog heaven (or human heaven, for that matter), but I didn’t trust myself to find the solid middle ground between bald fact and emotional comfort. I tried Goodbye Mog, but I couldn’t read it myself without dissolving into strangulated sobs, which defeated the purpose. (I grew up on Mog myself, and am frankly not yet ready for her to be dead.)

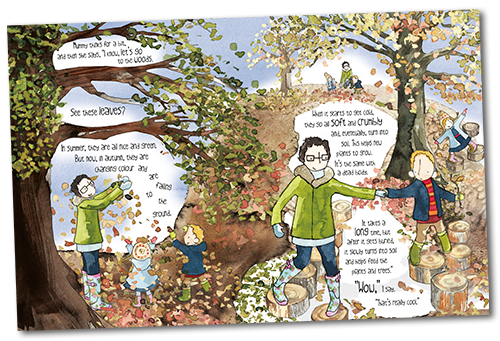

So I ordered an American book first published in the 1980s, called Lifetimes. This has a calm, inexorable tone throughout, and illustrations which evoke the beauty of death in nature – broken shells, ants, butterflies – as well as the vivid joy of being alive (although the pictures of people are a little dated now). “It is the way they live, and it is their lifetime,” is its refrain. I won’t say it’s a firm favourite of my daughter’s, but it provided me with a solid foundation, a simple, straightforward script – and it did seem to help when the poor old dog disappeared.

There’s a still more thought-provoking approach in the German book Duck, Death and the Tulip, in which Duck becomes aware, one day, that someone with a skull for a head, and a rather natty tartan coat, is following her everywhere. Eventually, she chums up with friendless Death, talking to him about the afterlife, and what will happen to her after she dies. Then she does die, and Death tends to her body, placing it gently in the river which carries it away.

Making peace with the idea of death as a constant companion, something that awaits everyone, and which is better reconciled with than feared, is an uncomfortable prospect for many parents; unsurprisingly, perhaps, since adults struggle with the idea too, sometimes till the end of their lives. But it might lessen the seismic nature of grief and fear a little, for both young children and adults, if we grew up with the idea of death as both inevitable and essential, instead of keeping it at arm’s length.

Which books did you read, either to prepare children or to help them navigate grief?

Published on Oct 21, 2014